Introduction to SIBO

Defining SIBO and Its Prevalence

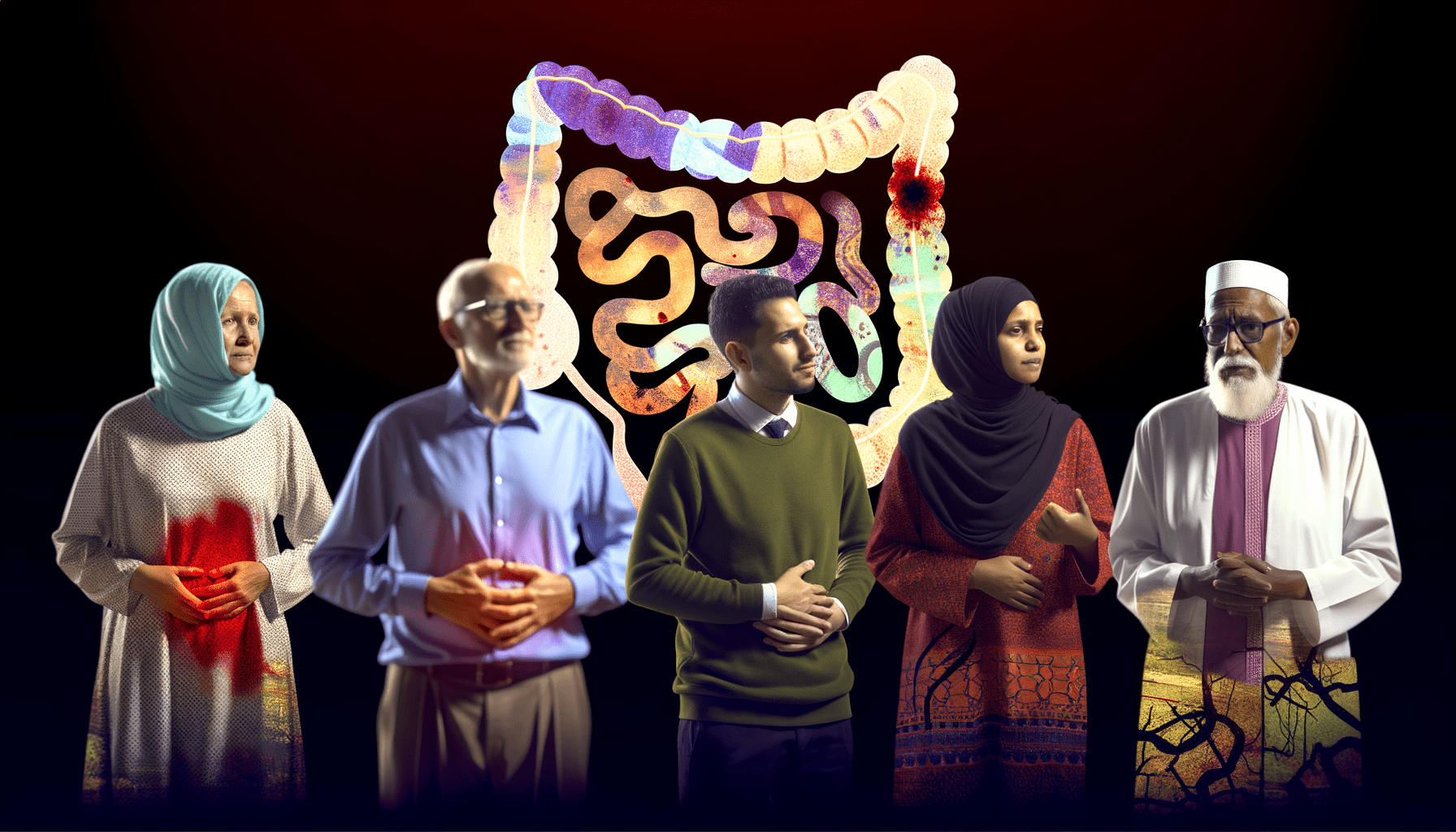

Small Intestinal Bacterial Overgrowth (SIBO) is a condition where excessive bacteria inhabit the small intestine, leading to gastrointestinal symptoms and malabsorption issues. While the small intestine normally houses a low level of bacteria, SIBO occurs when these numbers significantly increase. This imbalance can result in the malabsorption of nutrients and a variety of symptoms, including bloating, gas, abdominal pain, and diarrhea. SIBO’s prevalence is not fully understood, but it is believed to be underdiagnosed due to overlapping symptoms with other gastrointestinal disorders.

Common Misconceptions About SIBO

- SIBO is the same as IBS: While symptoms may overlap, SIBO and Irritable Bowel Syndrome (IBS) are distinct conditions. SIBO is characterized by bacterial overgrowth, whereas IBS is a broader diagnosis with various contributing factors.

- Only certain types of bacteria cause SIBO: In reality, SIBO can be caused by an overgrowth of various types of bacteria, not just “bad” bacteria.

- SIBO can be cured by diet alone: While dietary changes can manage symptoms and reduce bacterial overgrowth, they may not address the underlying cause of SIBO.

The Importance of Understanding SIBO

Understanding SIBO is crucial for several reasons. Firstly, it can lead to serious health complications if left untreated, such as vitamin deficiencies and weight loss. Secondly, it often requires a multifaceted treatment approach, including antibiotics, dietary changes, and addressing underlying conditions. Lastly, awareness of SIBO can help individuals seek appropriate diagnosis and treatment, improving their quality of life. As research continues to evolve, the medical community is gaining a better grasp of how to manage this complex condition effectively.

The Multifaceted Nature of SIBO

Symptoms and Conditions Associated with SIBO

Small Intestinal Bacterial Overgrowth (SIBO) is a complex condition with a wide array of symptoms that can often mimic other gastrointestinal disorders. The hallmark of SIBO is an abnormal increase in the number of bacteria in the small intestine, which can lead to:

- Bloating and abdominal discomfort

- Diarrhea or constipation, sometimes alternating between the two

- Nutrient malabsorption, resulting in deficiencies such as vitamin B12 deficiency

- Unintended weight loss due to malabsorption

- Systemic symptoms like fatigue, joint pain, and skin issues such as rashes

These symptoms can significantly impact the quality of life and may be exacerbated by diet, stress, and comorbid conditions.

The Role of Endotoxemia in SIBO Manifestations

The overgrowth of bacteria in SIBO can lead to endotoxemia, where bacterial endotoxins, particularly lipopolysaccharides (LPS), enter the bloodstream. This can trigger systemic inflammation and immune responses that contribute to the symptoms of SIBO. Endotoxemia is associated with:

- Increased intestinal permeability, often referred to as “leaky gut”

- Activation of the immune system, leading to inflammation both locally in the gut and systemically

- Aggravation of autoimmune conditions, as the immune system may become hyperactive

Understanding the role of endotoxemia is crucial for developing targeted treatments that address the underlying causes of inflammation in SIBO.

How SIBO Affects Different Body Systems

SIBO’s impact extends beyond the gastrointestinal tract, affecting multiple body systems:

- Nervous System: The gut-brain axis means that SIBO can influence mood and cognitive function, potentially contributing to conditions like anxiety and depression.

- Immune System: Chronic inflammation due to SIBO can lead to immune dysregulation, increasing susceptibility to infections and other immune-mediated diseases.

- Endocrine System: SIBO can disrupt hormone balance, affecting processes like insulin regulation and thyroid function.

- Integumentary System: Skin health may be compromised, with conditions such as eczema and acne being linked to gut health.

- Musculoskeletal System: Nutrient malabsorption can lead to deficiencies that weaken bone and muscle health.

Given the systemic nature of SIBO, a holistic approach to treatment is often necessary to restore overall health and well-being.

The Underlying Causes of SIBO

Bacterial Imbalances and Their Impact

The small intestine is designed to have relatively low levels of bacteria compared to the colon. However, in small intestinal bacterial overgrowth (SIBO), bacteria proliferate inappropriately. This overgrowth can damage the mucosal lining of the small intestine, leading to a condition often referred to as “leaky gut,” where pathogens and undigested food particles can enter the bloodstream, causing systemic inflammation and a variety of symptoms. The imbalance in bacterial populations can disrupt the normal digestive processes, leading to malabsorption of nutrients and contributing to deficiencies in vitamins and minerals such as iron, vitamin B12, and the fat-soluble vitamins A, D, E, and K.

Dietary and Genetic Factors

Diet plays a crucial role in the development and persistence of SIBO. Diets high in sugars, alcohol, and refined carbohydrates can promote the growth of pathogenic bacteria. Conversely, diets low in fermentable carbohydrates (FODMAPs) may help reduce bacterial overgrowth. Genetic factors may also predispose individuals to SIBO. For instance, genetic variations affecting the immune system can impact gut barrier function and the body’s ability to regulate bacterial populations in the small intestine.

The Impact of Other Gastrointestinal Conditions

Several gastrointestinal conditions are associated with an increased risk of developing SIBO. These include structural issues like blind loop syndrome, motility disorders that affect the movement of food through the intestines, and conditions that reduce gastric acid secretion, which normally helps control bacterial growth. Diseases such as Crohn’s disease, celiac disease, and diabetes can also impair gut motility and lead to SIBO. Additionally, the use of certain medications, such as proton pump inhibitors and immunosuppressants, has been linked to an increased risk of SIBO.

Understanding the multifactorial nature of SIBO is essential for effective treatment. Addressing the underlying causes, such as dietary modifications, managing associated conditions, and correcting nutrient deficiencies, is key to alleviating symptoms and preventing recurrence.

Variability in SIBO Presentation

Variation in Bacterial Species and Their Effects

The clinical manifestations of Small Intestinal Bacterial Overgrowth (SIBO) can vary significantly among individuals, which is partly due to the diversity of bacterial species that can colonize the small intestine. Different species have distinct metabolic activities and interactions with the host, leading to a range of symptoms and complications. For instance, some bacteria may produce excessive amounts of gas, leading to bloating and pain, while others may interfere with nutrient absorption, causing malnutrition and weight loss. The specific composition of the bacterial population in SIBO can also influence the severity and persistence of the condition, as well as the response to treatment.

Individual Differences in Gut Flora and Enzyme Activity

Individual differences in gut flora composition and enzyme activity can significantly affect the presentation and progression of SIBO. Factors such as genetic predisposition, diet, medication use, and previous gastrointestinal infections can all influence the gut microbiota. Variations in enzymes like lactase, which is responsible for breaking down lactose, can lead to different symptoms when certain bacteria ferment undigested lactose. Additionally, the presence of certain enzymes produced by the overgrown bacteria themselves can lead to unique metabolic byproducts, which may contribute to the symptomatology of SIBO.

The Significance of Gastrointestinal Tract Integrity

The integrity of the gastrointestinal tract plays a crucial role in the development and presentation of SIBO. A healthy, intact intestinal lining acts as a barrier to prevent bacterial translocation and maintain immune homeostasis. When this barrier is compromised, due to conditions such as chronic inflammation, celiac disease, or irritable bowel syndrome (IBS), it can predispose an individual to SIBO. The resulting increased intestinal permeability, often referred to as “leaky gut,” can lead to systemic immune activation and a wide array of symptoms beyond the gastrointestinal tract, including joint pain, skin rashes, and fatigue. The degree of gut integrity loss can therefore influence the clinical picture of SIBO and its associated systemic effects.

Diagnosing SIBO

Traditional and Emerging Diagnostic Methods

Small Intestinal Bacterial Overgrowth (SIBO) is a complex condition characterized by an excessive number of bacteria in the small intestine. Traditionally, the gold standard for diagnosing SIBO has been jejunal aspiration and fluid culture, which involves obtaining a sample from the small intestine and analyzing it for bacterial growth. However, this method is invasive, costly, and not widely available. Consequently, non-invasive breath tests have become the preferred diagnostic tool in clinical practice. These tests measure hydrogen and methane gases produced by bacteria in the small intestine and exhaled in the breath after the ingestion of a sugar solution. Emerging diagnostic methods include the use of serum biomarkers and intestinal fluid analysis through capsule endoscopy, which are still under investigation for their efficacy and reliability in diagnosing SIBO.

Challenges in Accurate Diagnosis

Accurate diagnosis of SIBO presents several challenges. The symptoms of SIBO are non-specific and overlap with other gastrointestinal disorders, making clinical diagnosis based on symptoms alone difficult. Additionally, the interpretation of breath tests can be complicated by factors such as improper patient preparation, dietary influences, and variations in individual gut transit times. False positives can occur due to contamination from oral bacteria or rapid transit to the colon, while false negatives may result from the use of antibiotics or prokinetic agents prior to testing. Moreover, there is no consensus on the optimal diagnostic criteria for breath tests, leading to variability in how results are interpreted among different healthcare providers.

The Role of Breath Tests in SIBO Detection

Breath tests are the most commonly used diagnostic tool for SIBO due to their non-invasive nature and relative ease of administration. The lactulose breath test (LBT) and the glucose breath test (GBT) are the two primary types of breath tests used. The GBT is considered more specific as glucose is absorbed in the proximal small intestine, reducing the likelihood of colonic bacterial fermentation affecting the results. However, the LBT can be more sensitive in detecting SIBO throughout the small intestine. During these tests, patients consume a sugar solution and breath samples are collected at regular intervals to measure the levels of hydrogen and methane. An increase in these gases suggests bacterial fermentation and, consequently, the presence of SIBO. Despite their utility, breath tests are not without limitations, and results should be interpreted alongside clinical symptoms and patient history for a conclusive diagnosis.

In conclusion, diagnosing SIBO remains a challenge due to the limitations of current diagnostic methods and the complexity of the condition itself. While breath tests offer a practical approach, they must be carefully administered and interpreted in conjunction with a comprehensive clinical evaluation to ensure accurate diagnosis and effective management of SIBO.

Managing and Treating SIBO

Conventional and Alternative Treatment Approaches

The management of Small Intestinal Bacterial Overgrowth (SIBO) involves a combination of conventional and alternative treatment approaches. Conventional treatments typically include the use of antibiotics such as Rifaximin, which targets the bacterial overgrowth directly within the small intestine. In some cases, prokinetics are prescribed post-antibiotic treatment to help prevent recurrence by improving gut motility.

Alternative treatments may include herbal therapies with antimicrobial properties, such as oregano oil, berberine, and garlic. These natural remedies can be as effective as antibiotics for some individuals and are often preferred due to their lower risk of contributing to antibiotic resistance. Additionally, alternative practices such as acupuncture and stress management techniques like meditation and yoga can support overall digestive health and address underlying issues that may contribute to SIBO.

Dietary Interventions and Their Efficacy

Diet plays a crucial role in managing SIBO, both during and after treatment. A low-FODMAP diet, which restricts certain carbohydrates that are prone to fermentation, can help alleviate symptoms. However, this diet is meant to be temporary as long-term restriction can lead to nutritional deficiencies and an altered gut microbiome.

Other dietary strategies include the Specific Carbohydrate Diet (SCD) and the Gut and Psychology Syndrome (GAPS) diet, which focus on removing complex carbohydrates that are difficult to digest. The efficacy of these diets varies from person to person, and careful reintroduction of foods is essential to maintain a balanced and nutritious diet.

The Importance of Personalized Treatment Plans

Personalized treatment plans are vital when managing SIBO due to the variability in symptoms, underlying causes, and patient response to treatment. A tailored approach should consider individual dietary tolerances, lifestyle factors, and the presence of coexisting conditions. Working closely with a healthcare provider, such as a gastroenterologist or a registered dietitian, ensures that the treatment plan addresses the unique needs of the patient.

Monitoring symptoms and making adjustments to the treatment protocol is an ongoing process. It may involve a combination of medications, dietary changes, and alternative therapies. The goal is to not only treat the current overgrowth but also to implement strategies that prevent recurrence, such as stress reduction, regular physical activity, and a balanced diet that supports gut health.

Ultimately, the management of SIBO is a multifaceted endeavor that requires a comprehensive and individualized approach to achieve long-term relief and maintain digestive health.

The Broader Implications of SIBO

SIBO’s Connection to Other Health Conditions

SIBO, or Small Intestinal Bacterial Overgrowth, is not just a condition that affects the digestive system. It has been linked to a variety of other health issues, indicating that its impact extends beyond the gut. For instance, SIBO has been associated with conditions such as irritable bowel syndrome (IBS), fibromyalgia, chronic fatigue syndrome, and rosacea. This suggests that the presence of excessive bacteria in the small intestine can have systemic effects, potentially triggering or exacerbating these conditions.

Preventative Measures and Lifestyle Changes

Preventing SIBO involves a multifaceted approach that includes dietary modifications, lifestyle changes, and possibly the use of prokinetics to improve gut motility. Diets low in fermentable carbohydrates, known as low-FODMAP diets, can help reduce symptoms and bacterial overgrowth. Additionally, regular physical activity and stress management techniques can improve gut motility and overall gut health. Avoiding unnecessary antibiotics and medications that disrupt the gut microbiome is also crucial in preventing SIBO.

Future Directions in SIBO Research and Treatment

The future of SIBO research looks promising, with a growing interest in understanding the complex interactions between the gut microbiome, the immune system, and the nervous system. Emerging diagnostic methods, such as comprehensive microbiome analysis, are being explored to provide a more accurate diagnosis of SIBO. In terms of treatment, there is a shift towards personalized medicine, where treatments are tailored to the individual’s specific gut microbiome profile. This includes the use of targeted probiotics, prebiotics, and fecal microbiota transplantation. Moreover, the development of new pharmaceuticals that selectively target pathogenic bacteria without disrupting beneficial microbes is an exciting area of research.