Achieve Your Goals: Research Reveals a Simple Trick That Doubles Your Chances for Success

This article is an excerpt from Atomic Habits, my New York Times bestselling book.

We all have goals. And what’s the first thing most of us think about when we consider how to achieve them?

“I need to get motivated.”

The surprising thing? Motivation is exactly what you don’t need. Today, I’m going to share a surprising research study that reveals why motivation isn’t the key to helping you achieve your goals and offers a simple strategy that actually works.

The best part? This highly practical strategy has been scientifically proven to double or even triple your chances for success.

Here’s what you need to know and how you can apply it to your life…

How to Make Exercise a Habit

Let’s say that — like many people — you want to make a habit of exercising consistently. Researchers have discovered that while many people are motivated to workout (i.e. they have the desire to workout and get fit), the people who actually stick to their goals do one thing very differently from everyone else.

Here’s how researchers discovered the “one thing” that makes it more likely for you to stick to your goals…

In 2001, researchers in Great Britain began working with 248 people to build better exercise habits over the course of two weeks. The subjects were divided into three groups.

The first group was the control group. They were simply asked to track how often they exercised.

The second group was the “motivation” group. They were asked not only to track their workouts but also to read some material on the benefits of exercise. The researchers also explained to the group how exercise could reduce the risk of coronary heart disease and improve heart health.

Finally, there was the third group. These subjects received the same presentation as the second group, which ensured that they had equal levels of motivation. However, they were also asked to formulate a plan for when and where they would exercise over the following week. Specifically, each member of the third group completed the following sentence: “During the next week, I will partake in at least 20 minutes of vigorous exercise on [DAY] at [TIME] in [PLACE].”

After receiving these instructions, all three groups left.

The Surprising Results: Motivation vs. Intention

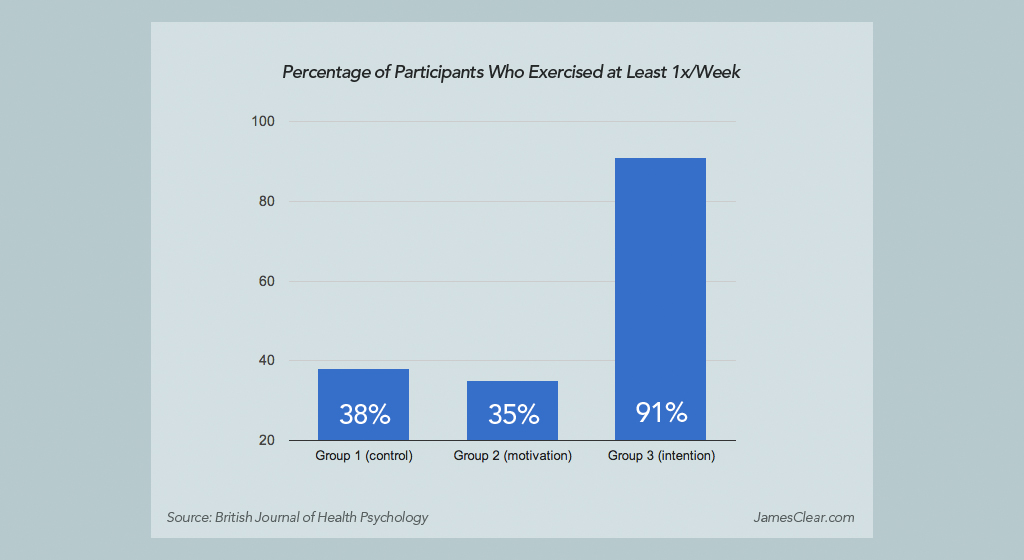

In the first and second groups, 35 to 38 percent of people exercised at least once per week. (Interestingly, the motivational presentation given to the second group seemed to have no meaningful impact on behavior.) But 91 percent of the third group exercised at least once per week—more than double the normal rate.

Simply by writing down a plan that said exactly when and where they intended to exercise, the participants in Group 3 were much more likely to actually follow through.

Perhaps even more surprising was the fact that having a specific plan worked really well, but motivation didn’t work at all. Group 1 (the control group) and Group 2 (the motivation group) performed essentially the same levels of exercise.

Or, as the researchers put it, “Motivation … had no significant effects on exercise behavior.”

Compare these results to how most people talk about making change and achieving goals. Words like motivation, willpower, and desire get tossed around a lot. But the truth is, we all have these things to some degree. If you want to make a change at all, then you have some level of “desire.”

The researchers discovered that what pulls that desire out of you and turns it into real–world action isn’t your level of motivation, but rather your plan for implementation.

Implementation Intentions

The sentence that the third group filled out is what researchers refer to as an implementation intention, which is a plan you make beforehand about when and where to act. That is, how you intend to implement a particular habit.

The cues that can trigger a habit come in a wide range of forms—the feel of your phone buzzing in your pocket, the smell of chocolate chip cookies, the sound of ambulance sirens—but the two most common cues are time and location. Implementation intentions leverage both of these cues.

Broadly speaking, the format for creating an implementation intention is:

“When situation X arises, I will perform response Y.”

Hundreds of studies have shown that implementation intentions are effective for sticking to our goals, whether it’s writing down the exact time and date of when you will get a flu shot or recording the time of your colonoscopy appointment. They increase the odds that people will stick with habits like recycling, studying, going to sleep early, and stopping smoking.

Researchers have even found that voter turnout increases when people are forced to create implementation intentions by answering questions like: “What route are you taking to the polling station? At what time are you planning to go? What bus will get you there?” Other successful government programs have prompted citizens to make a clear plan to send taxes in on time or provided directions on when and where to pay late traffic bills.

How to Follow Through With Your Goals

The punch line is clear: people who make a specific plan for when and where they will perform a new habit are more likely to follow through. Too many people try to change their habits without these basic details figured out. We tell ourselves, “I’m going to eat healthier” or “I’m going to write more,” but we never say when and where these habits are going to happen. We leave it up to chance and hope that we will “just remember to do it” or feel motivated at the right time. An implementation intention sweeps away foggy notions like “I want to work out more” or “I want to be more productive” or “I should vote” and transforms them into a concrete plan of action.

Many people think they lack motivation when what they really lack is clarity. It is not always obvious when and where to take action. Some people spend their entire lives waiting for the time to be right to make an improvement.

Once an implementation intention has been set, you don’t have to wait for inspiration to strike. Do I write a chapter today or not? Do I meditate this morning or at lunch? When the moment of action occurs, there is no need to make a decision. Simply follow your predetermined plan.

The simple way to apply this strategy to your habits is to fill out this sentence:

I will [BEHAVIOR] at [TIME] in [LOCATION].

- I will meditate for one minute at 7 a.m. in my kitchen.

- I will study Spanish for twenty minutes at 6 p.m. in my bedroom.

- I will exercise for one hour at 5 p.m. in my local gym.

- I will make my partner a cup of tea at 8 a.m. in the kitchen.

Give your habits a time and a space to live in the world. The goal is to make the time and location so obvious that, with enough repetition, you get an urge to do the right thing at the right time, even if you can’t say why.

What to Do When Plans Fall Apart

The best laid plans of mice and men often go astray.

—Robert Burns

Sometimes you won’t be able to implement a new behavior — no matter how perfect your plan. In situations like these, it’s great to use the “if–then” version of this strategy.

You’re still stating your intention to perform a particular behavior, so the basic idea is the same. This time, however, you simply plan for unexpected situations by using the phrase, “If ____, then ____.”

For example…

- If I eat fast food for lunch, then I’ll stop by the store and buy some vegetables for dinner.

- If I haven’t called my mom back by 7pm, then I won’t turn on the TV until I do.

- If my meeting runs over and I don’t have time to workout this afternoon, then I’ll wake up early tomorrow and run.

The “if–then” strategy gives you a clear plan for overcoming the unexpected stuff, which means it’s less likely that you’ll be swept away by the urgencies of life. You can’t control when little emergencies happen to you, but you don’t have to be a victim of them either.

Use This Strategy to Achieve Your Goals

If you don’t plan out your behaviors, then you rely on your willpower and motivation to inspire you to act. But if you do plan out when and where you are going to perform a new behavior, your goal has a time and a space to live in the real world. This shift in perspective allows your environment to act as a cue for your new behavior.

To put it simply: planning out when and where you will perform a specific behavior turns your environment into a trigger for action. The time and place triggers your behavior, not your level of motivation.

This strategy ties in nicely with the research I’ve shared about how habits work, why you need to schedule your goals, and the difference between professionals and amateurs. So what’s the moral of this story?

Motivation is short lived and doesn’t lead to consistent action. If you want to achieve your goals, then you need a plan for exactly when and how you’re going to execute on them.

This article is an excerpt from Chapter 4 of my New York Times bestselling book Atomic Habits. Read more here.

Sarah Milne, Sheina Orbell, and Paschal Sheeran, “Combining Motivational and Volitional Interventions to Promote Exercise Participation: Protection Motivation Theory and Implementation Intentions,” British Journal of Health Psychology 7 (May 2002): 163–184.

Peter Gollwitzer and Paschal Sheeran, “Implementation Intentions and Goal Achievement: A Meta‐Analysis of Effects and Processes,” Advances in Experimental Social Psychology 38 (2006): 69–119.

Katherine L. Milkman, John Beshears, James J. Choi, David Laibson, and Brigitte C. Madrian, “Using Implementation Intentions Prompts to Enhance Influenza Vaccination Rates,” Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences 108, no. 26 (June 2011): 10415–10420.

Katherine L. Milkman, John Beshears, James J. Choi, David Laibson, and Brigitte C. Madrian, “Planning Prompts as a Means of Increasing Preventive Screening Rates,” Preventive Medicine 56, no. 1 (January 2013): 92–93.

David W. Nickerson and Todd Rogers, “Do You Have a Voting Plan? Implementation Intentions, Voter Turnout, and Organic Plan Making,” Psychological Science 21, no. 2 (2010): 194–199.

“Policymakers around the World Are Embracing Behavioural Science,” The Economist.

Edwin Locke and Gary Latham, “Building a Practically Useful Theory of Goal Setting and Task Motivation: A 35-Year Odyssey,” American Psychologist 57, no. 9 (2002): 705–717, doi:10.1037//0003–066x.57.9.705

Thanks for reading. You can get more actionable ideas in my popular email newsletter. Each week, I share 3 short ideas from me, 2 quotes from others, and 1 question to think about. Over 3,000,000 people subscribe. Enter your email now and join us.

Weekly wisdom you can read in 5 minutes. Add the free 3-2-1 Newsletter to your inbox.